What inspired you to become a photojournalist?

I have always been fascinated by stories from the world’s remote corners. When I read or saw the reports of the great Italian reporters, such as Ettore Mo, Almerigo Grilz, Gian Micalessin, and Fausto Biloslavo, I wondered what it would be like to experience those situations firsthand. So, as soon as possible, I quit my job, packed my backpack, and left.

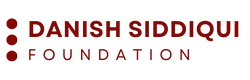

You have covered many wars and conflicts around the world. What have you learned from your experience covering these?

I documented a few conflicts in the peripheries of the world. The main thing I learned is always to trust your instincts. The first feeling in a given circumstance is the one to follow without second thoughts.

What has been your most challenging story?

Indeed, my most challenging reportage was when I first went to Mindanao, in the southern Philippines. There was no continuous war but a low-intensity conflict between the government army and various Muslim guerrillas, some of which were inspired by al-Qaeda and then by the Islamic State. Kidnappings were the main problem at the time.

A few days after I was there, while I was waiting to follow the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (Milf), one of the largest armed movements on the island, to their stronghold of Cotabato, word got out that there was a westerner in town. I had to stay hidden in a basement for three days. Then I managed to make good contact and do the report.

Which have been your most memorable stories?

Every reportage is a story you will carry with you for the rest of your life. Now that I am writing, I am reminded of a 2017 evening at the front in the town of Kominternovo (Donbass) with pro-Russian militias. It was payday, and rivers of vodka flowed in the trenches between mortars. It was a very long night that I will never forget because it was the first time that several bullets repeatedly grazed me.

How do you cope with reporting distressing and traumatic stories from conflict zones?

It is not easy. Because even if you are there to document, getting caught up in the stories you see is inevitable. But everyone has their role, and it is important to show the world even the most dramatic situations.

What kind of challenges do you face as a freelancer?

I can mainly speak about the Italian market, where I work the most. Unfortunately, freelancers are seen as second-rate journalists, not realizing that they add value to journalism who can still get to the heart of the stories. I think the biggest problem for a freelancer is making people understand the importance of a job done. Many times newspapers are interested in a reportage but want to underpay it, not understanding all the work behind it. Reportage does not start when you leave and does not end when you return. Before and afterward, there is a vast amount of work in research, contact tracing, and post-production.

You’ve written many books as well. Tell us more about them.

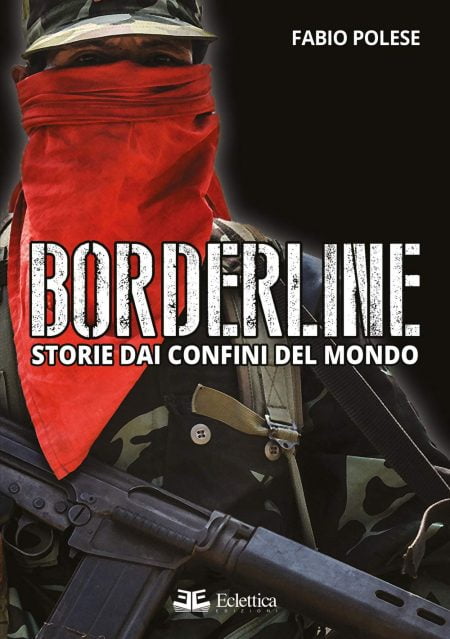

The latest is ‘Borderline. Storie dai confini del Mondo‘ (Eclettica Edizioni), where there are some stories I have documented over the years. In this book, a mix of journalistic reportage and personal feelings, I explain how I organized my travels, chose the stories to tell, and left. I also like to mention three other books. “I Guerrieri di Dio. Hezbollah Dalle Origini al Conflitto in Siria’ (Mursia), written with historian and great friend Stafano Fabei, where we retrace the history of the Lebanese Shia movement, ‘Strade di Belfast. Tra muri che parlano e sogni di libertà” (Eclettica Edizioni), where I recount the actuality of the Northern Ireland conflict through many photographs and the words of those who lived through the darkest years, and finally, “Sak Yant, Inchiostro Magico. Tatuaggi sacri Thai’ (Eclettica Edizioni), a book where I describe my journey into the Thai occult world, with many interviews and shots.

The latest is ‘Borderline. Storie dai confini del Mondo‘ (Eclettica Edizioni), where there are some stories I have documented over the years. In this book, a mix of journalistic reportage and personal feelings, I explain how I organized my travels, chose the stories to tell, and left. I also like to mention three other books. “I Guerrieri di Dio. Hezbollah Dalle Origini al Conflitto in Siria’ (Mursia), written with historian and great friend Stafano Fabei, where we retrace the history of the Lebanese Shia movement, ‘Strade di Belfast. Tra muri che parlano e sogni di libertà” (Eclettica Edizioni), where I recount the actuality of the Northern Ireland conflict through many photographs and the words of those who lived through the darkest years, and finally, “Sak Yant, Inchiostro Magico. Tatuaggi sacri Thai’ (Eclettica Edizioni), a book where I describe my journey into the Thai occult world, with many interviews and shots.

Where do you see freelance journalism heading in the future?

As mentioned before, the further you go, the more you have to understand that the freelance reporter is an added value who does not stop at the news but enters the news. He smells it; he listens to it; he photographs it and lives it.

What advice would you give future photojournalists or young photojournalists just starting their careers?

I recommend always fighting for what you want to do. At first, everything will seem gloomy and impossible, but it is not so. Do not lose heart at the first no’s or answers that do not come. Sooner or later, the “yes” will come if you have done a good job. Seeing your report published is a great satisfaction. Always trust your instincts in risky areas and organize your trips well. The real job is to get the right contacts and leave as safely as possible.

Work Portfolio: www.fabiopolesereporter.com

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by those interviewed by the Danish Siddiqui Foundation, including all program participants, are solely their own current opinions regarding events and are based on their own perspectives and opinions. The views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the Danish Siddiqui Foundation, or the companies with which any program participants/interviewees are, or maybe, affiliated.