Why did you choose to become a photojournalist?

Being a journalist means being open to all subjects and possibilities. My background was eclectic, and I was interested in history, politics, and the arts from an early age. Added to this is the desire to understand the world better and tell stories.

Which photographer has inspired you most and why?

This is a difficult question to answer. There were so many names that influenced and inspired me, but if I were to mention just one name, Lewis Hine, who has heartfelt work engaged in social causes and was able to change the legislation on child labor in the USA. Hine managed to convey through his photographs the harsh conditions of child labor and immigrants sensitively and movingly.

What has been your most challenging story?

At the beginning of my career, I accompanied a landless workers’ camp for a few days demanding agrarian reform. Over the time interacting with these people, I made beautiful images and was very well received by them. At a certain point, the court ordered the removal of the people who were camped there by the police. There was a lot of crying and despair on the part of the families, but it was a fulfilling moment for me to document that event as it was very distressing to share the suffering of those people.

And your most memorable stories over these 30 years of experience?

There are many stories over these 30 years, but one of the most memorable ones I can remember was accompanying the soccer player Pelé, a myth in Brazil, for more than a week. On the last day, he attended a dinner at a restaurant frequented by the country’s elite. Pelé met me at the restaurant door and walked in with arms around me. As we entered, the place stood still, and soon, they began applauding the country’s most incredible personality. Pelé pointed his hand at me as if I was the reason for all the commotion. I was paralyzed. But the worst thing about this story is that I don’t have any photos that are registered at the moment. The only available camera was attached to my neck.

Can you also tell us more about the two books Saga – Portrait of the German Colonies in Brazil and Terras de Preto – Stories of nine quilombola communities, which you’ve authored?

“Saga – Portrait of the German Colonies in Brazil” was my first experience as a photographer dedicated to a long-term shoot before becoming a professional photographer. In the early 1900s, large waves of Germans immigrated to the southern states of Brazil. They were small farmers who maintained the Germanic language and culture of an almost medieval Europe. I spent part of my childhood vacationing with my mother’s relatives who lived in one of those regions. I went to live in Germany when I was 18 on a cultural exchange program for one year. Germany is today one of the most modern countries in the world and has gone through two major world wars. The German communities in Brazil, opposed to all these events in their nation of origin and a tropical environment, seemed to me a fascinating theme undergoing a remarkable transformation. They inserted themselves in the modern world but held on to their culture and customs.

I found out about Quilombola communities during a professional assignment. They were formed by slave fugitives who ran away and moved to distant, hard-to-get places in Brazil. This was a part of history unknown to most people. When I started photographing these communities, the urban black movement was fighting for a law regulating the right to own land. I photographed the nine pioneering communities in this fight. Today it is known that hundreds enjoy this right. It was long-lasting work, going back and forth to these communities over almost ten years, with a great deal of personal involvement. I am very proud of this work. Some of my images were used by the Federal Attorney’s Office in defense of land ownership for these populations.

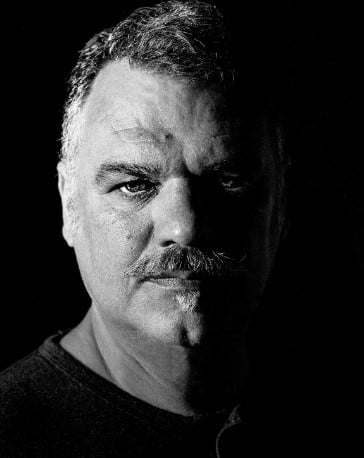

How would you describe our style of work? What do your photographs try to convey?

I am a photojournalist who first learned from an electrifying daily newspaper environment in a large metropolis. I have a classic look that seeks harmony even within a chaotic situation so that it can have the power to synthesize the subject addressed. It is possible to achieve this in a single image, but most of the time, it is done through rehearsal, and then the construction of a style happens from the development of the work. It is a dynamic construction where the images can talk to each other and assemble a coherent narrative in style while simultaneously communicating with all the power of synthesis that photography offers.

What do you enjoy the most about your work?

And what do you find the most challenging? The possibility of knowing different realities is one of the great benefits of our profession, whether in journalistic or corporate assignments. Having other points of view is an incredible learning experience. The biggest challenge is knowing how to adapt to different situations and clearly and objectively document what is in front of you.

How do you prepare before any assignment?

It is essential to be as informed as possible about what will be photographed. With the emergence of the internet today, this is much easier and more accessible. I do a lot of interviews and research before starting an assignment.

Which camera and lenses do you use?

Which are your favorites? My preferred lens is a 24/70mm -2.8 zoom in almost all situations. I also use another zoom, the 70/200mm with a 2.8 aperture. I’ve been using Canon cameras since the EOS line came out. I recently won the Sony Award in a contest, a Sony A7, a powerful camera in terms of resources that I use with the same type of zoom, but I’m still adapting to it. The difference in handling is enormous.

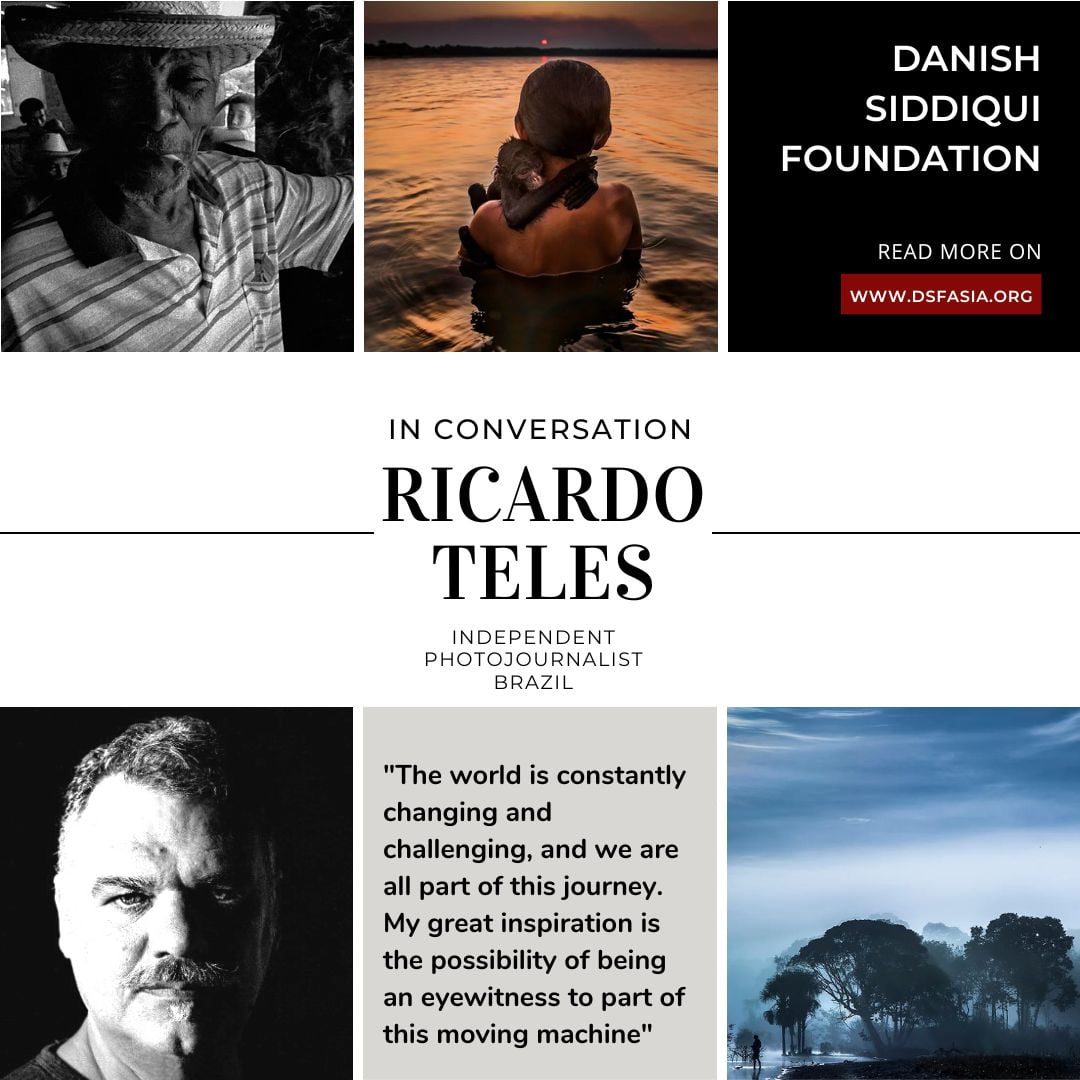

How do you keep yourself motivated and inspired

The world is constantly changing and challenging, and we are all part of this journey. My great inspiration is the possibility of being an eyewitness to part of this moving machine.

What does ethical photojournalism mean to you?

Ethics in photojournalism is part of ethics in life, how we behave in the most different situations according to the most basic principles of dignity. More specifically, in photojournalism, how we treat the result of our work, always with a commitment to the truth.

What advice would you give to aspiring photojournalists?

I already belong to a generation that is closing the door on a way of working that has lasted for decades. We attended different newsrooms and used negatives in a world that operated at a different speed than today. It has never been an easy profession, and it was never easy to gain recognition and space. The challenges are there, and the job market has changed while new possibilities emerge. But what never changes are the passion for telling stories through images.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by those interviewed by the Danish Siddiqui Foundation, including all program participants, are solely their own current opinions regarding events and are based on their own perspectives and opinions. The views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the Danish Siddiqui Foundation, or the companies with which any program participants/interviewees are, or maybe, affiliated.