How did your early experiences as a horse wrangler in Wyoming influence your decision to pursue photography and photojournalism as a career?

My lifelong love of horses inadvertently sparked my interest in photography and subsequently led to my career in photojournalism. While at University in England, I seized the opportunity to use my passion for horses by spending the summers working as a wrangler on a horse ranch in the US state of Wyoming. I was so inspired by the sight of a large herd of horses against the backdrop of the rugged mountains and incredibly diverse terrain that I was compelled to try and capture some of it with my camera.

At the time, I had a simple point-and-shoot camera and knew nothing about photography. When the ranch’s head wrangler Heath – a man of few words who I looked up to – told me he thought I had an “eye for photography” and suggested investing in a “real” camera, I was extremely encouraged, and the seed was firmly planted. From then on, I started to take a much more serious interest in photography and did indeed invest in my first “real” DSLR camera.

Your work covers various subjects, from humanitarian and environmental crises to political conflicts. How do you approach each project and ensure your photography effectively communicates the stories behind these issues?

I always begin by researching to understand the context of the issue, which, of course, is crucial. I then make a mental wish list of the images I think would best illustrate the story I want to tell and do my best to capture a wide variety of photos I can select from in the editing process. That will generally include some portraits, environmental images to give an idea of the context, some close-up images that highlight details, and a good variety of action shots.

Generally, I approach each project by seeking out the human element to illustrate the story through the perspective of an individual or group of people. I try to speak to as many people as possible and then capture images that highlight their story.

Your photography is known for its powerful storytelling. How do you capture the essence of a moment and convey emotions through your images?

As photographers, we’re always looking to capture a shot that will impact and grab attention. However, it’s a fine line between capturing and conveying emotions and being intrusive in the moment, which may be very emotional and difficult for the person or group of people we photograph. The main thing is to work with sensitivity and compassion while anticipating how best to capture the sentiment of the moment, be it celebratory, sad, or any other emotion. Capturing positive emotions is inherently easier than those of adversity and suffering, which carries responsibility and requires a greater amount of sensitivity to avoid being exploitative or intrusive. Conveying emotions requires getting close to people without interfering in the moment. That’s why having good people skills and understanding how to capture people’s emotions without affecting or exploiting them are so important in photojournalism.

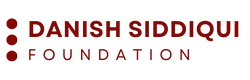

In practical terms, I find being ready to capture the moment is obvious but equally important. I try always to have the right camera settings for the environment and circumstances, so when I see the moment, I don’t lose time adjusting the exposure settings. It’s also important to be able to adjust settings instinctively and very quickly. One of the most challenging shooting environments I’ve worked in was the field clinic near the frontline in Mosul, Iraq, which was a dark, poorly lit abandoned storefront that required completely different exposure settings to the bright daylight outside. It was there that I developed my skills in adjusting my settings very quickly. Otherwise, I would have ended up with a lot of under and over-exposed images!

What challenges do you face as a photojournalist working in conflict zones or other dangerous environments, and how do you ensure your safety while capturing important images?

There are, of course, many challenges and inherent risks working in any active conflict zone or hostile environment. An important part of our job as photojournalists is to be cognizant of those risks and to mitigate them to the best of our ability. In practical terms, that means having the right protective gear – body armor and helmet – and a combat first aid kit. More important is having formal hostile environment training to know how to administer first aid for the kind of wounds you might expect to encounter in a war zone.

I always find it extremely helpful to speak to locals and other journalists who have been working in the area to get an idea of what the situation is and what the risks are. Another fundamentally important thing in conflict zones is working with a good fixer. While I was based in Iraq, I worked with several incredible fixers, both men and women, without whom I wouldn’t have been able to do my job. They carry an enormous amount of responsibility, and we rely on them for securing access to hostile areas, interpretation, and guidance on what the risks are, among other things. I think fixers often don’t get the recognition they deserve for the incredible and dangerous work they do.

Being aware of the impact on our mental health is also very important, as is finding ways to process things. Personally, I find spending time in the countryside, especially in Wales and Wyoming, to be particularly healing. Being close to nature and being around animals helps me in many ways, and I think it keeps me mentally balanced and grounded.

Your photography often sheds light on underrepresented communities and issues. How do you approach gaining the trust and consent of the people you photograph, especially in sensitive or vulnerable situations?

I think one of the most important things as a photographer is simply to be a good person, to work with sensitivity, understanding, and empathy, and to never put the profession ahead of our humanity. I always try to treat people how I want to be treated and make sure I show respect and cultural sensitivity.

Consent is, of course, of utmost concern, as is ensuring the people we photograph fully understand how the photos will be used and where they may be published. It’s also my responsibility to ensure the photos I take will do no harm to the person photographed. Very often, that means capturing images that don’t reveal the person’s identity.

I can easily relate to how being photographed can make a person feel uncomfortable – I personally much prefer being behind the camera than in front of it, so I always try to make the person I’m photographing feel comfortable in my presence. Of course, it always depends on the context. In the middle of a field clinic on the frontline in Mosul, for example, things are moving so quickly that there often isn’t a lot of time to get to know the people. There, I photographed many children who had been injured in the fighting, and those images are quite graphic. I believe that such photos, although they’re difficult to look at, are important in confronting people with the raw reality of war and how it affects the most vulnerable.

For projects where there is more time, I never lead with my camera. I try to get to know people first, to create a connection with them. Very often, that means sharing some food or a cup of tea. What I love most about being a photographer is having the opportunity to get to know people from diverse backgrounds and cultures and learn about their lives. It’s a great privilege to be then able to share their stories through photography.

I also always make it clear that it’s no problem at all if they prefer not to be photographed. I think that’s very important. I never put pressure on anyone to be photographed.

You have worked with various editorial clients, international organizations, and major publications. How do you balance artistic expression with meeting your client’s specific requirements and expectations?

Understanding and meeting the client’s specific requirements is always the principal consideration, of course. Each client has different requirements, so I tailor the type of images I capture to meet their needs while also staying true to my core principle of accurately and sensitively reflecting reality.

I always try to capture a wide variety of images; some are directly linked to the story or project I’m working on, and others may offer a more artistic reflection that can be found even in the midst of crises and conflicts.

Your recent recognition in the Amnesty International UK Media Awards highlights the impact of your work. Can you share a particular project or story that has had a profound effect on you?

I’m delighted and honored to have my work recognized in the Amnesty Media Awards. It really inspires me how impactful and effective photography can be in drawing attention to important issues and sometimes, if we’re lucky, contributing to positive change. That’s what drew me into photojournalism many years ago while volunteering in Ghana.

As a twenty-something graduate, I traveled to West Africa to work with a community-based organization that supports vulnerable people living with HIV/AIDS. During the project, I took pictures of some of the women who are supported by the organization. It was then that I began to appreciate the potential of my own photographs to draw attention to an issue, in this case, the plight of vulnerable women and children living with HIV/AIDS in rural communities. The pictures also helped raise money for a fundraising campaign I set up to provide beds for the women who, until then, slept on the cold, bare ground. That project in Ghana definitely had a profound and lasting impact on me.

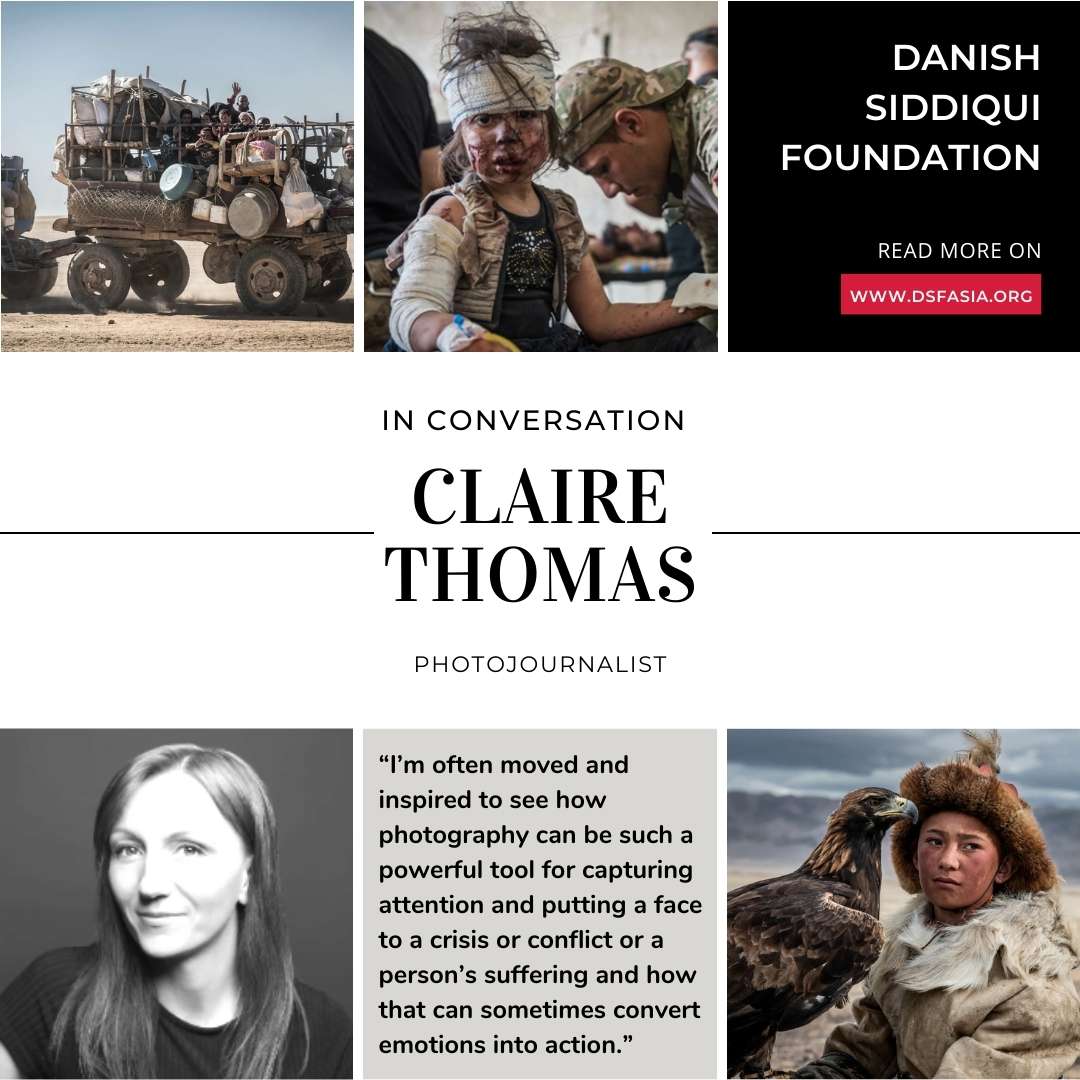

I’m often moved and inspired to see how photography can be such a powerful tool for capturing attention and putting a face to a crisis or conflict or a person’s suffering and how that can sometimes convert emotions into action.

Last year, I created a fundraising campaign for a ten-year-old Yazidi girl in Iraq who suffers from a terrible skin disorder called Epidermolysis bullosa. After I shared some photos online that I’d taken of her (with her and her parents’ consent, of course), the fundraiser took off and raised over £7,000 in less than 24 hours. It’s now reached over £10,000, which has drastically changed Maya’s life for the better. This project, too, highlights the power of photography in creating change in a person’s life, which means so much to me and is what I appreciate most about being a photographer.

As a judge in international photography competitions, what criteria do you consider when evaluating the work of other photographers? What advice do you have for aspiring photojournalists looking to make a meaningful impact with their photography?

The criteria, of course, depend on the category I’m judging, whether the work is being evaluated on the merit of a single image or a series of images, in which case the storytelling aspect would be a greater consideration. Whatever the category, I consider the composition of each image, its visual impact, whether it is properly exposed, whether it raises questions or conveys an emotion… For some awards, the impact of the photo or photos is also a consideration, so it’s important to explain that well in the description. What I don’t like to see are images that are overly manipulated in post-production.

I would advise aspiring photojournalists to focus on stories or issues they’re interested in and gather content to highlight them. It’s sometimes difficult, if not impossible, to measure the impact of our work, so I would say it’s good to focus on the photography and capturing compelling and emotionally evocative images instead of thinking too much about the potential impact.

I often find it emotionally challenging to tell the stories of people who have suffered or are suffering tremendous difficulties while knowing that it’s not in my power to help them directly. Sadly, that’s the nature of photojournalism. It isn’t our job to resolve the problems of the people we photograph; rather, it’s our job to draw attention to those problems in the hope that those who have the power to make change will be compelled to do so. However, small acts of kindness and compassion can go a long way on an individual level.

Traveling to remote and diverse corners of the world must have its unique challenges. Can you share a memorable experience or encounter during your independent photography projects?

I feel extremely lucky that my work takes me to many remote and beautiful parts of the world. Since my first visit to Mongolia in October 2019, I’ve grown increasingly fond of the wild and wonderful country. One of my favorite experiences, both personal and professional, was having the opportunity to ride alongside a Kazakh father and son who are both eagle hunters in the Altai mountains of Mongolia. It was a few hour’s ride from their home up into the mountains where they train their eagles to hunt foxes and other small animals, and during that ride, I captured one of my all-time favorite images, titled Kazakh Riders, which shows Alankush and his son Arkalak carrying their eagles while riding horses. Seeing twelve-year-old Arkalak ride his horse so proudly while his enormous eagle flew back onto his arm was an unforgettable sight. Carrying a heavy camera and trying to use it while riding a horse over rough terrain isn’t easy, so I was very pleased (and perhaps a little surprised) by the results of those images.

With the advancements in digital technology and social media, photography has become more accessible than ever. What are your thoughts on the future of photojournalism and its role in shaping public awareness and social change?

I think photojournalism and reporting, in general, is more important than ever. Despite the volume of images we consume, I think there’s always an appetite for powerful, professional, and emotionally evocative photography. Also, with the rapid rise in AI-generated imagery, I think photojournalism has an increasingly important public awareness role by ensuring the content that’s consumed in the media is produced by credible photojournalists, not by computers.

In addition to your photojournalism, you are also a fine art photographer. How do you balance these two aspects of your photography, and how does each inform the other in your creative process?

I believe that photojournalism and fine art photography can complement each other. My approach to fine art photography is grounded in my passion for storytelling since my goal is to offer an authentic and artistic expression of reality and, as such, a bridge between photojournalism and fine art.

One of my favorite photographers is Steve McCurry, whose work I’ve admired for many years. I love how artistic his images are while also telling a story about a person or a place. That’s been a tremendous inspiration to me.

What advice would you give to photographers aspiring to create impactful photo essays or stories that can bring attention to pressing global issues?

I always advise aspiring photographers to develop their own visual voice by getting out to shoot whatever they’re drawn to document. I think when you’re passionate about something, it comes through in your work. I would say that some of my best work is related to my love of horses combined with my passion for photography.

When I started out as a freelance photojournalist, I reached out to several experienced photojournalists whose work I admired to ask for some advice and guidance. I studied Politics at University, so I didn’t have any formal training in producing photo essays or creating impactful stories. I quickly learned there’s no real roadmap to success as a freelance photojournalist, so I reached out to Jason Tanner, a fellow Welsh photographer whose work I admire, to ask for some guidance. I was very lucky to have his support and advice throughout my career, which has been and continues to be, extremely helpful.

I started by doing a few freelance assignments with local newspapers in Wales until I decided to travel to the Middle East, where I began producing photo essays about life in the West Bank and the daily struggles faced by Palestinians living under Israeli military occupation.

Once the skill of telling a story through photos is mastered, it can be applied to any story or issue anywhere in the world. So I would say the most important thing is to practice as much as possible and, above all, be persistent.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by those interviewed by the Danish Siddiqui Foundation, including all program participants, are solely their own current opinions regarding events and are based on their own perspectives and opinions. The views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the Danish Siddiqui Foundation, or the companies with which any program participants/interviewees are, or maybe, affiliated.