Why did you choose to become a photojournalist?

I became a photojournalist because I wanted to try and understand the world through visual language and how history has shaped so much of where we are and who we are today and explore that continuum.

Which photographer has inspired you most and why?

I don’t have a particular photographer who has inspired me more than others. Still, I’d say it’s a collective of photographers all with very distinct and unique styles, and whose primary focus ranges from photographing survivors of domestic abuse Donna Ferrato to Saul Leiter’s observations of color, light, and shapes to Gerda Taro, Gilles Peress, to Yang Yankang’s body of work on Tibetan Buddhism. Viewing the world through different formats and mediums, from fashion to art, to photography, is incredibly important to inform ourselves about visual language.

What has been your most challenging story?

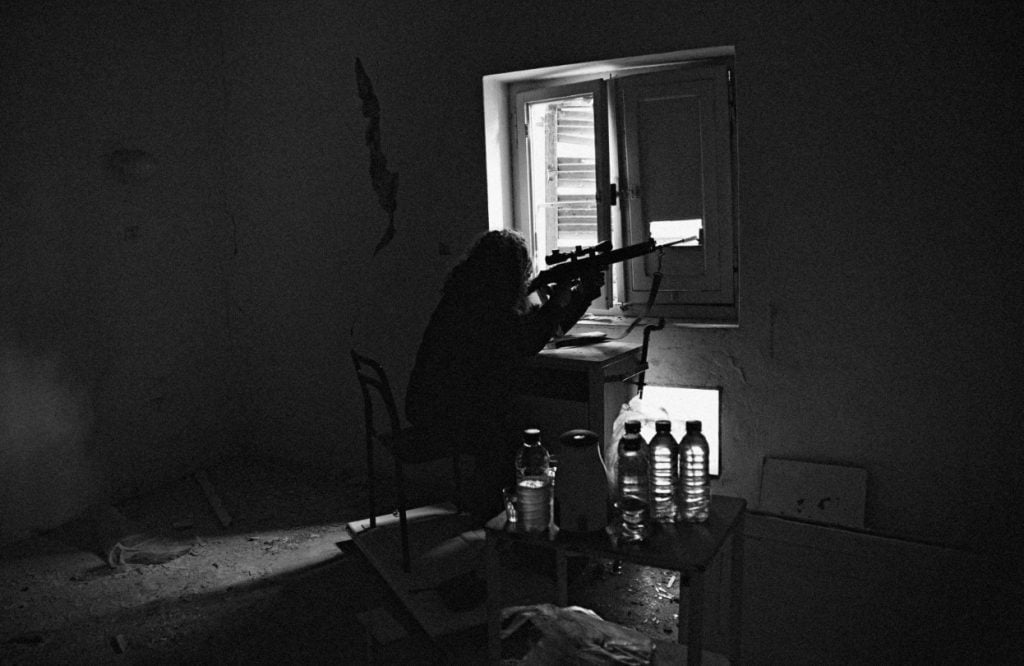

There is no particularly challenging story I can think of, but one country I have covered for a decade has undoubtedly proved challenging on many levels, Syria. On one level is the severe humanitarian suffering that continues there, with the war now in its 11th year – and this only appears to worsen each time I return – on another is the complexity of the conflict in which there are so many parties and proxies to the war that a solution to ending it is so beyond imagining. And another level is the difficulties in working there because of the logistical and safety challenges of operating in such an environment. And lastly, it is the widening gulf between the dissemination of information and stories from Syria and the continued, or worsening, apathy to the conflict there.

And your most memorable stories?

Many memorable assignments, but I remember small gestures the most. I was outside a church in Izium, Ukraine, just a day or two after Ukrainian forces retook it. A resident who had lived through the Russian occupation just came up to me and gave me two souvenirs: one was a church bell with a graphic of Izium on it, another was a card with a picture of a saint on it and a prayer written on the back. She didn’t say much but just offered it. There is so much horror in the places photographers/journalists go, but people’s kindness and warmth never cease to amaze.

You’ve covered many conflicts around the world. How has it influenced you as a photojournalist?

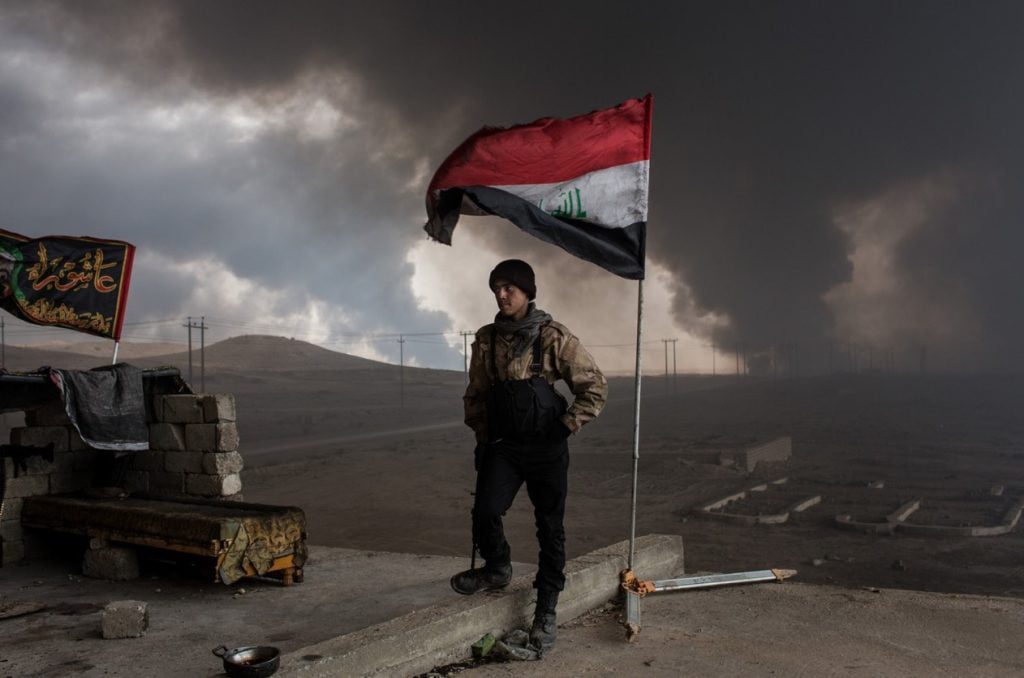

Covering conflicts in various countries around the world influenced me because I can see things more contextually now than when I first started. I think seeing the bigger picture – and being able to conceptualize stories in such a way without missing the importance of the human side of it.

How would you describe your style of work? What do your photographs try to convey?

My work style is very photojournalistic because the images are focused on people in their environment at that moment. I encompass the emotional side of what I am witnessing in the images.

What do you enjoy the most about your work? And what do you find the most challenging?

I enjoy most the privilege and ability to have time with people who inhabit so many different social strata, cultures, and living histories – to see how they move through the world, often under the most difficult of circumstances. What’s challenging is defying the apathy for these stories because they often seem to be in faraway places.

How do you prepare before any assignment?

Before each assignment, I research and brainstorm what I will focus on. I think of what’s important in a certain place and how that can be translated into a visual. Obviously, in hostile environments, many more logistical preparations are involved, thinking about roads, transportation, safety, checking in, equipment, and things like that.

How do you manage stress and work pressures?

I think earlier in my career, I was under the impression that I could keep going, and there is a sense of invincibility when you’re younger (I was 24 when I started covering active conflicts). Of course, with time, you realize that trauma and exhaustion compound themselves, and not taking the time to process and reflect, and taking the time not to do completely serious things, is necessary to balance the pressure.

Which camera and lenses do you use? Which are your favorites?

I’m currently using a Leica SL-2 with a 24-70mm lens and a Leica Q2. Both are my go-to cameras because of how intuitive they are for me, and the textures and colors of the files seem to fit well with my vision and how I want my images to be presented.

Which social media platforms do you often use(please share links), and how have they helped you?

I use Instagram, mostly (instagram.com/nicoletung). Most people now consume their news and content purely through social media, so when I pose images, and people see them and react or feel something, that is the new self-publishing ‘front page.’ As long as photography can impact or make people stop and think, that is the function of social media for me.

How do you keep yourself motivated and inspired?

This is similar to the question above – keeping a balance, a life at home that can be somewhat insulated little from everything I see and witness in the field.

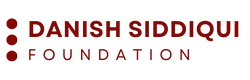

What does ethical photojournalism mean to you?

Ethical photojournalism is about respect and dignity of the people we photograph and trying to convey things in an understanding way – as much as possible

What advice would you give to aspiring photojournalists?

For aspiring photojournalists who wish to work in conflict zones – my best advice is to have first aid or hostile environment training. Knowing how to protect and potentially save those who work near and around you is the best thing we can do, next to consistently thinking about ethics.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by those interviewed by the Danish Siddiqui Foundation, including all program participants, are solely their own current opinions regarding events and are based on their own perspectives and opinions. The views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the Danish Siddiqui Foundation, or the companies with which any program participants/interviewees are, or maybe, affiliated.